Is it just low back pain? Or is it a slipped disc or a pinched nerve or sciatica? Do I need to rest or just stretch? Or will I have to live with it forever?

Low back pain is a common condition experienced by people of all ages. There’s approximately a 5-25% chance that you might get low back pain at some point through the ages and the prevalence increases with age. Hence it makes sense to be equipped enough to manage it.

Is it “normal” to experience low back pain at some point?

Low back pain is uncommon in the first decade of life, but prevalence increases steeply during the teenage years; around 40% of 9–18-year olds in high-income, medium-income, and low-income countries report having had low back pain.

Most adults will have low back pain at some point. The median 1-year period prevalence globally in the adult population is around 37%, it peaks in mid-life, and is more common in women than in men. Low back pain that is accompanied by activity limitation increases with age.

Looking at the bright side, 90% of acute LBP cases resolve within one month and the best evidence suggests around 33% of people will have a recurrence within 1 year of recovering from a previous episode and about 60-80% over a lifetime, although the number is high, the recurrences are usually not serious.

What could be the cause of my low back pain?

Only about 1-5% of back pain is caused by serious disease or injury that may include traumatic injury that may cause a fracture, back pain associated with urinary retention, loss of power and sensation in the limb, back pain linked to fever, unexplained weight loss or a history of malignancy. In such cases, a doctor's screening to scan and plan out appropriate treatment is required.

If none of these symptoms are present, then you are likely to be in the 95% of people who are classified as having non-specific low back pain where the specific nociceptive (pain) source cannot be identified

That can also be explained as the presence of tension, stiffness and soreness in the back with the inability to reliably test and identify a specific source of pain. However, it doesn't deny the existence of a source, simply put, as pain is multifactorial no matter the location, the same applies here.

A systematic review of 41 diagnostic studies found that the prevalence of diagnosable structural causes (e.g. disc, facet joint, SIJ) in people with LBP varied widely and could not be reliably identified using current clinical tests.

Does severe pain mean serious damage in the back?

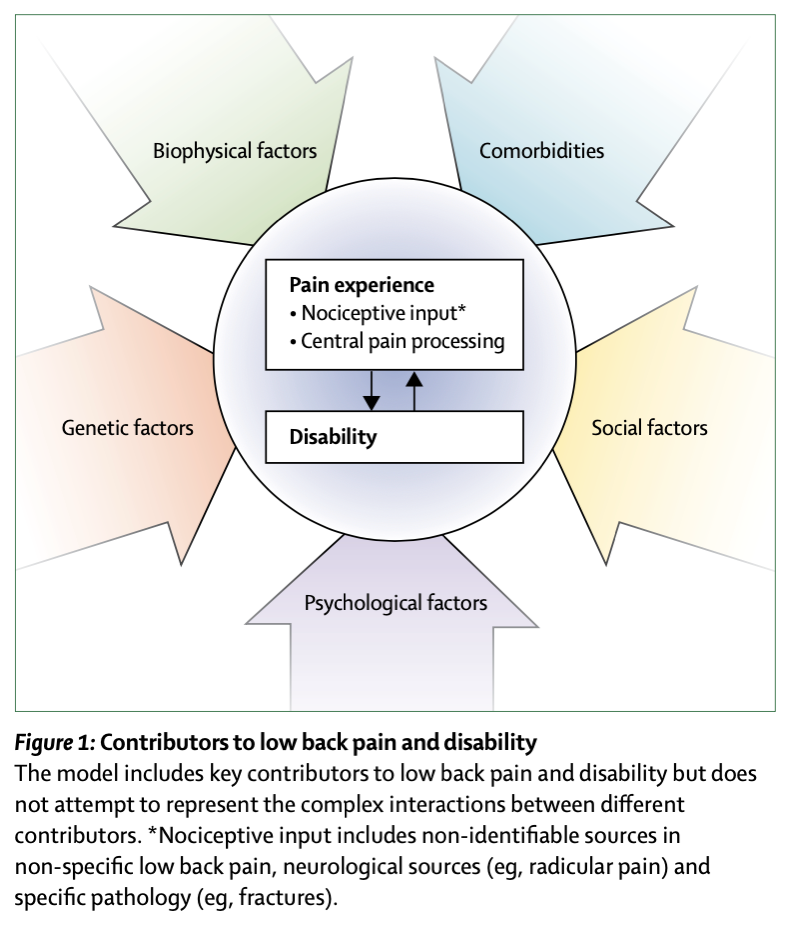

The severity of pain does not correlate well with the amount of tissue damage. As pain is multifactorial, influenced by biological, psychological, social, and environmental factors as well as our beliefs, a fusion of these factors together decides the amount of pain an individual experiences.

Hence, a person can have severe pain despite minimal tissue damage if they are experiencing high levels of stress and/or lack of sleep and/or if they had a painful episode of LBP in the past and/or any comorbidities or they can have minimal pain despite significant tissue damage.

How can unhelpful beliefs contribute to pain?

Unhelpful beliefs may lead to unhelpful behaviors such as avoiding: normal spine postures (ie, slouch sitting), movement (ie, flexing the spine), and meaningful activities (ie, spine loading, physical activity, social activities, and activities of daily living and or work). They may also lead to unhelpful protective behaviors such as muscle guarding, bracing ‘core’ muscles, and slow and cautious movement.

Unhelpful beliefs about LBP are associated with greater levels of pain, disability, work absenteeism, medication use, and healthcare seeking. Unhelpful beliefs are common in people with and without LBP and can be reinforced by the media, industry groups, and well-meaning clinicians. Add to it the fear of not knowing the reason for the same, if it is something sinister, how long it takes to get better, and what can be done to make it better, altogether can make the condition worse and can impact the prognosis.

Will finding the source of the pain help treat the pain better?

Evidence is insufficient to know whether MRI findings can be of use to predict the future onset, or the course, of low back pain.

Unnecessary imaging can cause harm. Misinterpretation of imaging results by clinicians could result in unhelpful advice (e.g. staying off work) and a cascade of medical interventions (Lemmers et al., 2019; Webster et al., 2013; Webster et al., 2014).

For example, asymptomatic disc degeneration is common and so unnecessary imaging could trigger overdiagnosis and the overuse of ineffective and costly treatments (e.g. lumbar fusion surgery). Therefore, MRI in isolation shouldn’t influence your treatment.

Some structural labels may carry negative connotations, and influence recovery expectations and beliefs about work and physical activity as well as lead to fear, worry, and avoidance of movement. For example, the label ‘degeneration’ may convey to a patient that their back is fragile.

Findings such as disc degeneration, arthritis, disc bulges, fissures, protrusions, and spondylolisthesis are very common in the pain-free population. The actual clinical importance of these structural findings is debatable. For example, a systematic review (33 studies, 3310 asymptomatic individuals) concluded that the prevalence of disc bulge was 30% in 20-year-olds, 60% in 50-year-olds, and increased to 84% in 80-year-olds amongst asymptomatic individuals, whilst the prevalence of disc degeneration amongst asymptomatic individuals increased from 37% in 20-year-olds to 90% in 80-year-olds.

Importantly, no evidence exists that imaging improves patient outcomes and guidelines consistently recommend against the routine use of imaging for people with low back pain.

How relevant is a posture in managing my LBP and preventing recurrence?

As discussed in previous blogs, there is minimal evidence that any particular posture is causative, protective, and preventative of back pain. While some postures may be painful to hold, this often reflects the level of sensitivity of the spine which may be associated with various biopsychosocial factors.

Fear of movement can lead to protective habitual behavior or guarding. For eg. bracing of the core that allows the spine to stay rigid and prevent any movement can further exaggerate the pain like holding a clenched fist for extended periods can cause discomfort irrespective of the presence of prior pain in hand. Thus, relaxation and postural variableness throughout the day can have a positive impact.

The authors of one such study conclude, “sitting posture that entails flexion of the lumbar spine causes more fluid to be expressed from the lumbar disc than do the erect posture. The effect is particularly marked in the nucleus pulposus. The fluid flow in flexed posture is sufficiently large to aid the nutrition of the lumbar disc.”

Therefore, adopt a posture that feels the most comfortable to you, keep varying it throughout the day, and if sitting with a slouch feels better, don’t shy away!

What if it is a pinched nerve/ sciatica?

Pinched nerve/sciatica, is an informal term commonly used to describe pain going down the leg which may or may not be accompanied by a sensation of pins and needles or numbness. It is termed so because it is believed that the sciatic nerve going down at the back of the leg is affected.

In reality, the sciatic nerve is formed by a bunch of nerves coming out of the low back, and irritation of one or many of those can cause sciatica-like symptoms.

According to the books, if you have pain (that can be also explained as pins and needles, sharp shooting, lancinating, shocking, or electric-like) down the leg that is associated with an irritated nerve in the low back, that is called lumbar radicular pain. If you have numbness or a loss of strength because of the same irritated nerve, that’s called lumbar radiculopathy. But they can often happen together, hence sciatica is a term casually used to describe either these or both of these conditions.

Disc herniation is the most common cause of sciatica, and inflammation of the affected nerve seems to be the critical pathophysiological process behind it rather than just plain old compression.

However, evidence demonstrates that disc herniations heal over time in about 3-12 months. Lumbar disc herniation can regress or disappear spontaneously without surgical intervention. Moreover, most cases of disc herniation resolve within a few weeks after the onset of symptoms.

Results of systematic reviews by Chiu et al in 2015 and Zhong et al in 2017 show that the higher the grade of disc herniation type, the higher the rate of spontaneous regression.

Furthermore, Karppinenet al in 2001 reported that “the degree of disc displacement in MRI did not correlate with sciatic symptoms.”

Additionally, there is a high probability of resolution of pain irrespective of whether the disc heals or not.

Will moving make it worse?

Best rest is a thing of the past. We have ample evidence available now that shows the rather positive effect movement has on our body, specifically speaking, on our spine.

Running, cycling, and lifting weights are all activities that are healthy for the discs and the spine.

A recent study compared the spines of 18 height-matched non-sporting referents to 18 high-volume cyclists who have cycled 150km/week for at least the past 5 years, which is a significant amount of time spent in sustained flexion. They found that high-volume cyclists had better intervertebral disc tissue quality than otherwise healthy, but non-sporting, people. This was characterized by greater disc height and longer T2- time (i.e. better hydration and glycosaminoglycan content), particularly in the nucleus pulposus.)

Movement doesn’t have to be complicated and there are no specific exercises that work surely for low back pain. Contrary to popular belief, exercise works in many more ways like decreasing tissue sensitivity and improving overall health rather than just strengthening the area.

Keeping that in mind, walking is a relatively simple way to integrate movement into your daily life that doesn’t require any prior experience or supervision even when you are in pain. You can start with just 5 minutes a day to 30 minutes over time, increasing to 5 minutes per week. To make it challenging with time parameters like distance covered, uphill movement, and the number of steps, time can be increased, which can also be tracked easily.

Conclusion

Pain is very individual, what works for someone might not work for someone else and there is no cure-all strategy out there as of yet. However, that is the positive side of it because it provides us with a wide spectrum of options to choose from, adapt to, or modify according to each person. So don’t worry if the generic advice that you came across didn’t work for you.

For more go to Physio Explored Blogs

Cover Photo by cottonbro from Pexels

Disclaimer: This blog is for educational purposes only.

Comments